by Sam Tackeff | Dec 7, 2011 | Books

I believe that it is really important to never stop learning, and more importantly to actively seek out new learning opportunities. I think we all get into a rut sometimes, which is why it is so fun to make yourself happy by choosing to learn something new. I divide my learning into a few different categories:

1. Short term experiences. The idea here is to expose myself to many different things in sort of quick blasts. A lot of these are through taking a lesson of some type in order to learn the basics of a new skill or activity. Say, taking two weeks to try out new exercise classes, reading a book on a topic that I know absolutely nothing about, taking a cooking class, learning to play a handful of tabs on the guitar, finding someone who has a garden and needs a weeder.

Ultimately, some of these experiences will lead to:

2. Long term passions. These are the things that take a lifetime to develop. I like creating actionable projects to help me develop my passions. This blog is one of those projects. The Tea Project is one too. Another passion (without a real project) is developing my photography skills.

I’m particularly interested in food photography. With photography (and almost everything else in life), the key to learning is doing. It does help to have some fundamentals though. Classes are expensive, but incredibly worth it. A few years ago I took a class with Penny De Los Santos, and it was shocking how much a few hours of killer instruction changed my life. (Yes, my life.)

Another way I keep myself doing is having a camera on me at all times. It doesn’t have to be my Lumix (which I adore, for the record)– it can also be the technology that I keep in my pocket at all times: my smart phone. I love taking photos with my phone. I don’t have an iPhone, so I can’t use Instagram (sadness.), but I have a lot of fun using RetroCamera and FXCamera.

I also spend a lot of time reading about food photography online. CreativeLive is a great resource that I’ve been spending a lot of time on. They have free streaming classes, and the ability to purchase previously recorded ones. (I’m a little bitter that I didn’t buy Penny De Los Santos’ food photography class while it was on sale). MattBites, Wrightfood, and White on Rice Couple are a (very small) handful of some of the phenomenal blogs I draw inspiration from.

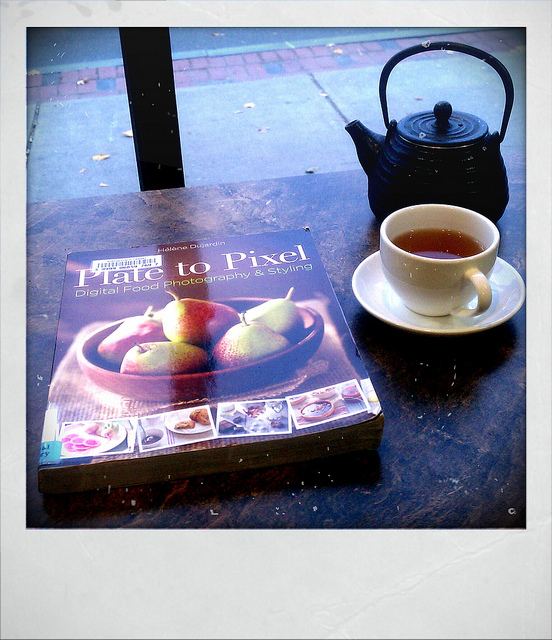

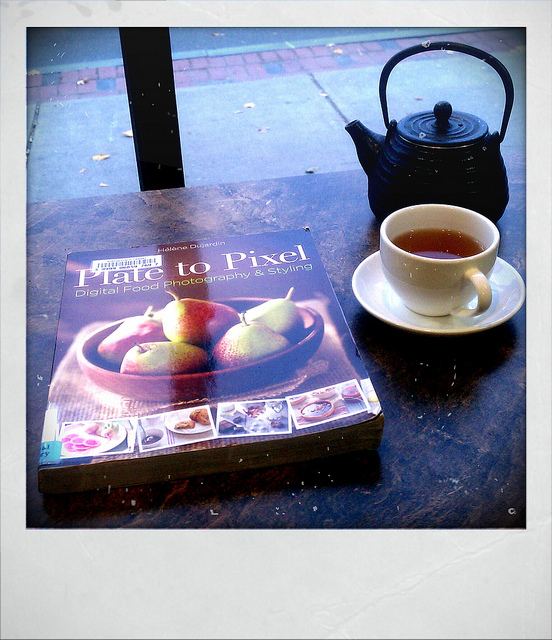

And finally, I love to read physical books. I take a lot of them out of the library – art books, technical books, and really constructive resources. This week, I’ve been reading Plate to Pixel – Digital Food Photography & Styling by Hélène Dujardin. Hélène writes and styles a beautiful blog: Tartelette – and I really admire her expertise and ability to share her knowledge. Plate to Pixel covers photography techniques, lighting, and styling. The book is not over-technical, and good for anyone ranging from skilled photographers who want to transition to food, to people who still can’t manage to take their thumb out of the frame. I think it would make a pretty great gift as well.

I’d love to hear about how you are learning too. What are your passions? What do you want to experience (for the first time) next?

by Sam Tackeff | Aug 22, 2011 | Books, Writing

“It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it… and then the warmth and richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied… and it is all one.”

— M.F.K. Fisher (The Art of Eating)

I have a few rituals for when I get into a rut with food. When I can’t think of what to cook any more, I sit down surrounded by my favorite cookbooks, and make lists. When I can’t think of what to write anymore, I read M.F.K. Fisher. For me, her writing is comforting. Like a stand-by recipe you know will turn out perfectly every time, but each time you cook it, it surprises you with new complexity. A new taste or thought. A new memory. Or a new connection.

Mary Frances Kennedy (M.F.K) Fisher, is generally considered one of the founders of modern food writing. For me, she is the ultimate authority.

Now, lest we ignore our predecessors, there has been food writing for millenia. The Greeks, the Romans, the Egyptians, they certainly knew how to throw a party, and enjoy their food and drink. But somehow, in the past several hundred years, there has been a drought of evocative food writing. The genre suffered a long spell of being largely prescriptive and dry. Either you were writing about how to give dubious elixirs to invalids, or you were giving technical details about mother sauces. Stray from these directions and you would be swiftly smote by the culinary deities. There wasn’t much more than that.

M.F.K Fisher was radically different. She wrote about food from the perspective of someone who passionately loved eating food. She wrote about indulging, traveling for food, taste, dreaming about food. She was blunt, exceedingly witty, and intelligent. How many food writers are expansive enough that their quotes fit seamlessly into Roger Ebert’s film reviews? Reading her writing, I’m always reminded of F.Scott Fitzgerald in tone and style – except instead of writing about disaffected wealthy people, she writes about quelling her own hunger, which is a much more interesting topic. She wasn’t a professional chef (and some of the recipes in her early books were slightly off), but boy could she conjure up a taste memory.

And that’s what modern food writing is about. Good food writing, that is. Fisher’s writing is about thinking about food, not from a technical standpoint, but a heartfelt one. If you are interested in improving your writing, M.F.K. Fisher is a good place to start.

Almost all the food writing I love and devour – the books, blogs, gushing articles in Saveur, even Ruth Reichl’s dream-like food tweets “Silver sky. Breezy. Cooler. Tiny red new potatoes gently roasted. Shower of salt, sweet green garlic. Soft, savory. Irresistible.” which spawned ½ of @RuthBourdain’s satirical tweets: “El Bulli just served its last dinner. Sources tell me Ferran shut off the lights in the middle of dessert and played “Don’t Stop Believin’.” – is indebted to M.F.K. Fisher.

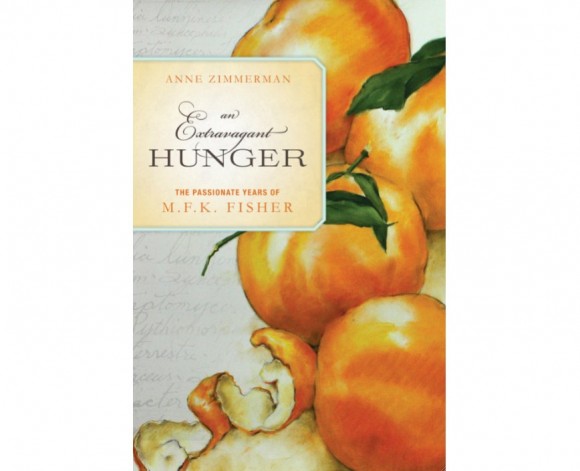

I could spend my time writing about M.F.K. Fisher ad nauseum, but this post is actually about Anne Zimmerman, whose biography of Fisher’s early life came out this year.

I met Anne a few years ago soon after I moved to San Francisco. She was finishing a book about the aforementioned food writer, Fisher, and I was managing a bookstore that specialized in books on food. I’m truly in awe of anyone writing a book, but Anne seemed particularly sweet and humble about it. I knew within about five minutes of meeting her that I would enjoy her writing.

Anne Zimmerman’s “An Extravagant Hunger” relates the story of M.F.K. Fisher’s fascinating rise to fame and prominence. Beyond her writing, Fisher was a riveting persona. By gathering details from her personal correspondence and papers, Anne brings to us the woman behind the writing, and it is easy to see Anne’s admiration of her subject in the text. A dramatic life, rife with tumultuous romance, passion and creativity, the food writing iconoclast is truly a phenomenal character.

There is no doubt that Fisher was a brilliant and talented young woman, however she didn’t hit her stride until her early thirties when her first book was published. From then on, she was incredibly prolific. She penned more than 30 books about food, and countless articles, as well as the best translation of Brillat Savarin’s ‘The Physiology of Taste’.

For all of us writers who have yet to publish our first book, it is encouraging to read about the meandering path it takes to be a true renaissance woman.

An Extravagant Hunger: The Passionate Years of M.F.K. Fisher by Anne Zimmerman

Published by Counterpoint, 2011

352 Pages

And if you need to get started on Fisher – I’d go ahead and recommend ‘The Art of Eating‘ which is a compilation of some of her best work.

by Sam Tackeff | Apr 8, 2011 | Books, Vegetables

It’s nice to have a muse, and for the past few months mine has been the lovely Penelope. Transplanted right from the Odyssey into the de Young, here she is surrounded by bountiful bouquets and looking particularly serene. Despite the fact that rumors are swirling of her husband’s death in far lands, she sits, awaiting his return, the symbol of fidelity and faith.

Yes, I understand that my life hasn’t been nearly as dramatic. But like Penelope, I had been existing in a state of limbo, and trying to be as calm and patient as possible and accept things as they came. And then my computer died abruptly (more about that here) so my patience was tried in whole new ways. To put this in perspective: in response to a recent email of mine, my grandmother responded “Dear Sam, you really have to go to the computer every day or you do not know what is up!”. (Hmm….)

Well, back to my story. For the last two years I’ve been living and breathing Omnivore Books. My day job was as the manager of this fairy tale wonderland, and I am so thankful to have been part of its growth. But as with everything in life, there is a natural course, and for me it was time to move onto new things. “Move on” being a loose term given that I still live five blocks away and will be around for many of the events anyway. But I won’t be there every day, and that realization comes in pin pricks when I think about it, and my heart breaks just a little bit each time.

Many days I am terribly sad to have left, mostly because I miss all of the wonderful people that are part of this community I’ve helped to build. I’m afraid that there will be acquaintances lost in the cracks because I’ve neglected to remember their last names, or they live a less digital life, or because I’m phenomenally bad at keeping in touch with people that I really do want to keep in touch with. Which reminds me, if you are on Twitter, and I, @alphaprep , don’t follow you, please let me know so we can keep in touch that way.

Then I remind myself that the bookstore is still there for me when I need it, and this little break has only made me appreciate the place more.

Now for the good news – my patient waiting paid off! I have a brand new job which is particularly fulfilling. I now work for a company called Square. It’s a financial company that allows anyone to accept credit card payments with their mobile phone (either to take money from your friends – or you know, for legitimate business). There are no fees to sign up, no monthly fees, and the device is free. But, lest I continue sounding like an advertisement, I’ll quit here and just say that it’s awesome to be working for a growing company with a product I truly believe in.

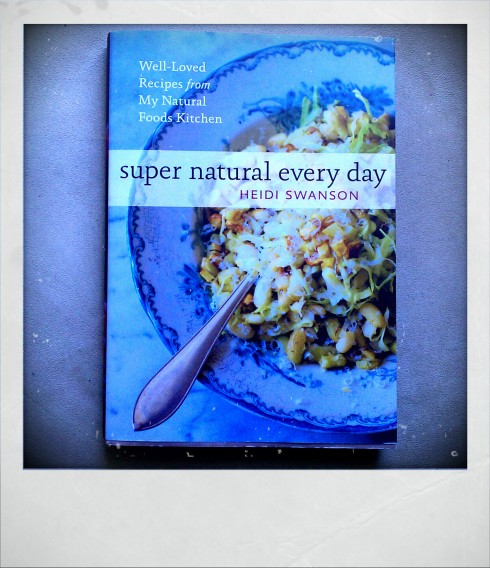

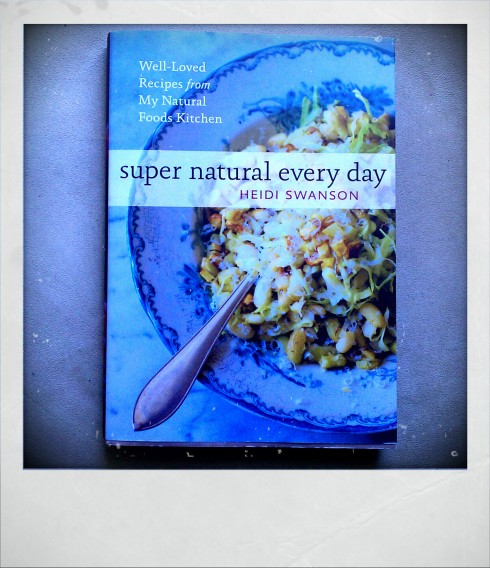

Another perk is that I get fed at work. (Breakfast, lunch, and if I so choose, dinner.) Although, this makes me a little nervous, because free tasty food is the bane of my healthy existence. Which is where this book comes into play. Just a few weeks ago, Heidi Swanson published her new book Super Natural Every Day, and I’ve been cooking and eating out of it as much as I can. Her recipes are utterly delicious while at the same time being very healthy – the perfect antidote to potential pitfalls of not cooking many of my daily meals. (I’m happy to say that in my first week of work, I did not, in fact, gain the five pounds I anticipated, but lost three.)

Heidi Swanson is one of those people who understands how to cultivate a beautiful life, and is uniquely adept at sharing it with others.

I first met Heidi at Omnivore, which to most would seem like a probable place to meet her, but believe me, I was still startled at the occurrence. (Yes, I know her blog is called 101 cookbooks. As in the very same type of book shelved along every wall of the particular establishment that I worked in.) But you know, it didn’t occur to me that she would actually end up in the same room as me, let alone would I get the privilege of seeing her on a semi-regular basis.

After meeting her just once, I ran into her at a coffee shop one evening by Duboce Park. She was drinking beers with her boyfriend Wayne, and I was positively overwhelmed by the fact that she not only remembered who I was, but both knew my name and gave me a hug. At that moment I realized how real this person was, and it seemed like a very San Francisco moment – where the people you aspire to be are real people, and you can realistically run into them in the course of your daily life on this 7 x 7 mile patch of Northern California.

It has been a pleasure to see Heidi over the past few years as she has come into the shop and gathered inspiration for her work in progress.

I was particularly excited to get my hands on an advanced copy of her new cook book (thank you Ten Speed!). The day mine came in the mail, I took it with me to one of my favorite spots in the city, Coffee Bar, and read it through cover to cover. And then I started cooking. Within the next few days, I would go on to make the green lentil soup (curry powder, brown butter, coconut milk, chives) on p. 149; the farro soup (curry powder, lentils, salted lemon yogurt) on p. 128; the weeknight curry (tofu, coconut milk, seasonal vegetables) on p. 135, which satisfied even the more carnivorous one in the house; and a bowl of lemon-zested bulgur wheat (coconut milk, toasted almonds, poppy seeds) on p. 37, which was the perfect start to my morning.

The best part of this book is that it is impossible to read without wanting to head straight to the kitchen. The recipes are easy enough that you could feasibly make them on the fly with a well-stocked pantry. (Which she teaches you how to create if you don’t yet have one.) The recipes are vegetarian, although so well layered with flavor that even the meat and potatoes crowd will enjoy them.

Last month we had a potluck at Omnivore, in honor of Heidi (and her new book). I had a truly lovely time taking up my old post – ringing up books, popping open Prosecco bottles and stealing moments to give and get hugs. I did a measly job of taking photos, but this whole wheat chocolate chip skillet cookie was one of my favorite dishes to photograph and eat. It’s actually not in the book, but the recipe is on Heidi’s site here.

It’s been quiet on here lately, but this book was a great reason for me to mosey on back. It’s nice to be here, in my little corner of the internet, and I’ve missed it – and I have missed you all.

by Sam Tackeff | Dec 11, 2010 | Baking, Books, Chocolate, Cookies

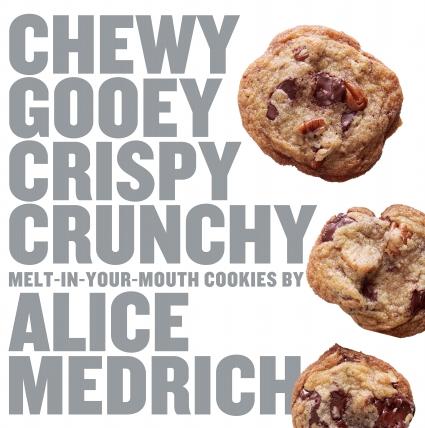

There are some cookbooks I read at the shop and fall madly in love with, but refuse to take home until I can no longer resist them because I know that I’m doomed when I do. Doomed! [Don’t worry, they win out at the end, I assure you.] Alice Medrich’s ‘Chewy Gooey Crispy Crunchy Melt-In-Your-Mouth Cookies‘ is one of those books.

This is because if there is any problem worse than my “cook-book problem”, it is my “cook-ie problem”. I am the type of person who will eat an entire batch of cookies if proper safeguarding precautions are not taken. And, as I’ve been giving in a little too often to my cookie problem, the one pair of jeans that I can still fit into are threatening to burst. I’m holding out as long as I can, damn it.

Alice came to Omnivore to talk about the book, and after spending a whole hour with the Goddess of Chocolate, it has taken every effort of mine not to bring it home and immediately start baking. My resolve was even further weakened by actually eating cookies made from the book:

For the talk, Celia made her Alfajores, a sweet and slightly crispy Latin American cookie filled generously with dulce de leche. Crispy and Gooey? Yes, please! She tweaked the recipe slightly to add some nuts and a little bit of extra salt. I had four, and would have had more had my mother not ingrained the principle of sharing. This was difficult. Had I been only a *slightly more selfish* and greedy person, there would have been none left in minutes.

A few reasons why you need this book:

1. It’s by Alice Medrich. **(see below)

2. The broad organization. The book is a play on textures and flavors. You get to choose from Crispy, Crunchy, Chunky, Chewy, Gooey, Flaky, and Melt in your mouth. Alice Medrich is a “crispy” girl. I’m a “chunky” girl myself. Yes, I said that. The more chocolate hunks or nuts, the better.

3. It’s all in the details. “Cookies seem deceptively simple. But success with cookies is success in the details,” Alice noted. When you give the same recipe to ten cookie bakers, even experienced ones, you might just come out with ten completely different versions.

This book seeks to streamline your baking. If you can conquer at least some of the variables, you will make better cookies. A user’s guide, quick start, FAQ’s, ingredients, equipment, are all there to make cooking baking more precise and successful.

The quick start gives the five most important details about successful cooking baking: amounts of flour, types of flour, oven temperatures, preheating the oven, and types of baking sheets. The FAQ’s go into even more detail about basic ideas: how to toast nuts, why you would chill cookie dough, what the best way to flatten dough, etc.

And yes, Alice Medrich wants you to get a scale. (And so do I. I got mine at Ikea for 12 dollars. What are you waiting for?) The measurements in the book are also in cups, but using a scale will give you great, consistent results.

4. The “Smart Search”. Even better than just an index, there is a brilliant section called the “smart search”. Need Wheat-free cookies? She lists the 40 or so options for you. Whole-Grains? Dairy-free? Ditto. Ridiculously Quick and Easy? Same. Don’t have time to bake during the holiday season? Well, there’s a whole list of ‘Doughs that Freeze Well’ and ‘Cookies that Keep At Least 2 Weeks’. Yes, there are even low-fat. Although, I’ve become wise to understand that low-fat doesn’t in any way mean that you should eat the whole batch.

5. Simplicity. After 8 cookbooks, things are getting more do-able for the home-cook. That doesn’t mean that she skimped on the fun stuff. “Anything I do, I need to learn something, and I need to teach something,” Medrich says. There are classics, and new twists on old favorites. “I didn’t want it to be something that an ordinary home baker with kids wouldn’t want to pick up and bake from”.

6. Well tested recipes. If you are familiar with any of her older cookbooks, including her IACP winning book ‘BitterSweet‘ you know first hand that her recipes work. When she wrote her first cookbook, she did a huge series of ‘Side-by-Side’ testing in a kitchen with a friend to compare how they interpreted the written recipes, and tweak to get more consistent results. (A fairly genius idea.)

Medrich also teaches cooking classes. “The teaching helps, because I do the recipes and get to see what questions come up.” Teaching is also useful to help a recipe writer guide the reader in the recipes. Learning how people interpret words on the page teaches her to be a better writer and learn to use more specific explanations. And the difficult part of testing? “First, too much tasting, and second, knowing when to stop.”

7. Well written recipes. Often, recipes take for granted things that are intuitive if you’ve had a lot of practice in the kitchen, and the author forgets to write down steps that the novice might not yet know. When you read through any of Alice Medrich’s recipes, it’s like you have a perceptive friend guiding you through things, so you don’t forget the basics while under fire.

It was rumored that Julia Child once said to Flo Braker “Write what works for you, Dearie”, and Medrich re-emphasizes that. “The good writers are the ones who ignore how it’s always been done and explain it in a way that makes sense to them.”

8. The personal touch. Alice has been on the set since book one cooking and styling her own dishes for the photo shoots. (For those less familiar with cookbook production, this is rarely the case). “It’s the thrilling part of the process in this book!” she said.

** While it’s important to focus on the merits of the cookbook itself, I take great pleasure in knowing the history of cookbook authors. It sweetens the deal when you get to use a book written by an inspirational (and smiling!) woman like Alice Medrich.

The Backstory:

When Alice Medrich was twenty, she went to Paris. It was there that Mme. Estelle, her land-lady, taught her about the Truffle, “that smooth, bittersweet statement about chocolate” that unbeknownst to her, would lead her to great things.

Upon coming back to Berkeley, her future still unclear, she opted for the rational lifestyle choice of putting off the real world… and heading to business school. Given that I almost went to business school right after graduating college, I can understand the impulse. (Though I’m glad I didn’t.)

At business school, she spent her free time making cocoa dusted chocolate truffles for the new Pig-By-The-Tail, Victoria Wise’s charcuterie shop. It didn’t take long to realize that she was becoming more interested in creating a dessert repertoire than dealing with case studies, and soon dropped out of b-school.

Before opening a pastry shop, Medrich did her due diligence. She headed back to Paris to take classes at Lenôtre, the famed pastry school, where she was often the only woman in her pastry classes.

She learned timing, temperature, and the physicality of multiplying recipes by trial-by-fire: at Pig-By-The-Tail, she would come up with a weekly special at the beginning of the week, an elaborate pastry that could be pre-ordered by six lucky customers. Without actually knowing if it would work, Medrich set about learning the recipes as she went – theoretically she would get enough practice by the end of the week to make at least six!

In 1976, she opened her shop, ‘Cocolat’.

I’ve heard more than one Bay Area native wax poetic about Cocolat and moan desperately about Alice’s legendary truffles. Celia (@omnivorebooks) used to head to the shop with cash from her co-workers in each pocket to pick up a bounty on her breaks. Mary (@mcs3000) recalled saving money to buy Alice’s first cookbook and making her Strawberry Carrousel Cake.

As a newcomer to San Francisco, it’s stories about shops like Cocolat that make me regret having not grown up here. By the time I moved here, Cocolat was no longer. (Pig-By-The-Tail, and Fran Gage’s Pâtisserie Française are others that I tragically missed out on.) I can’t live my life dwelling upon the fact that I’ve lived in the wrong era, but stories about the truffles and Cocolat’s ‘Reine de Saba’ make it hard not to. Another good reason for cookbooks like ‘Chewy Gooey” to help keep a legacy alive!

Alice’s Quick Bites:

That’s a lot of chocolate! In the early days, it wasn’t so easy to find quality ingredients. She used to send friends and family to purchase all the Ghiradelli Semisweet chocolate from the supermarkets (the best you could find at the time), until she realized that she used enough to get wholesale. Soon, Fifty pounds of chocolate wasn’t enough, and by the time she opened Cocolat, she was getting 300, even 500 pounds a month of chocolate delivered to her door!

Her favorite baking chocolates? “The most important thing is to use what you like the taste of. I still use Scharfenberger, because I like the taste a lot,” Alice says. (While I love using Valrhona myself, for chocolate chips I use Ghiradelli 60% cacao, which are flatter discs because of a higher fat content.)

Who eats all the recipes she tests? Her neighbors have been next door from her for more than thirty years, and they don’t accept treats anymore. (She fondly remembers the day that they sat down and ate an entire cake together.) Nowadays she gives them to whoever will take them – the new neighbors on the block, the synagogue down the street, a friend’s softball team.

On Inspiration: Inspiration comes from everywhere. Sometimes easily: “A lot of new recipes come from a recipe that is good already rather than a recipe you want to fix.” Other times, more abstractly: “I once developed a recipe from a salad from one of Paula Wolfert’s cookbooks.”

Her next project: Already in the works, a baking book for people more comfortable with cooking than with baking. Recipes that work the way cooks work, with a little bit more flexibility.

Chewy Gooey Crispy Crunchy Melt-in-Your-Mouth Cookies

by Alice Medrich

384 pages

Artisan Books

http://alicemedrich.blogspot.com/

by Sam Tackeff | Oct 22, 2010 | Baking, Books, French Fridays

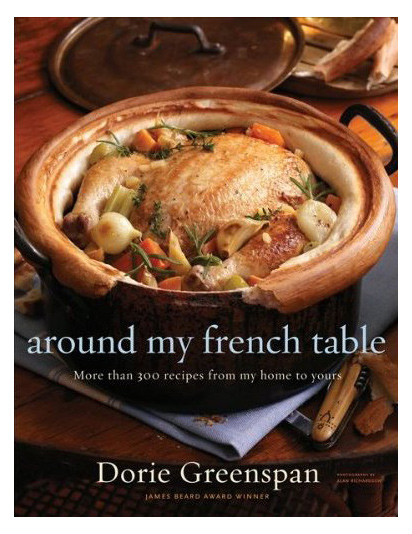

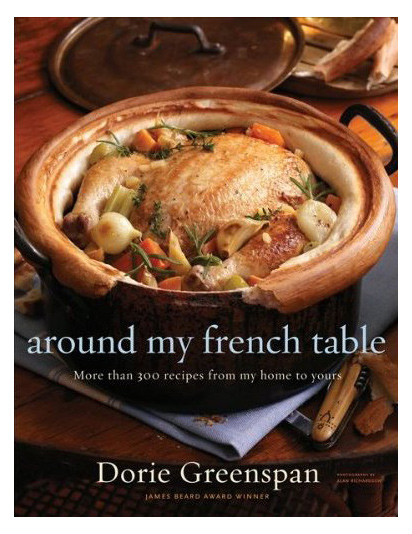

[First there was ‘Tuesdays With Dorie‘, where each week food-lovers across the internet united to bake a recipe from Dorie Greenspan’s ‘Baking: From My Home to Yours‘. And now Dorie is out with a wonderful new cookbook ‘Around My French Table‘ where she shares her favorite French recipes, and I’ve decided to cook along. Check out French Fridays with Dorie if you’d like to join the fun.

This week’s recipe was Hachis Parmentier – what Dorie describes as “a well-seasoned-meat-and-mashed potato pie that is customarily made with leftovers from a boiled beef dinner, like pot-au-feu. Her headnote in the recipe attributes inspiration from the famed chef, Daniel Boulud, who despite spending his days cooking luxurious meals at his haute cuisine restaurants, thinks of nothing better than going home and eating Hachis Parmentier – the perfect comfort food.]

Michael Chiarello was at Omnivore Books this week, and said something I believe to be very wise: “Taste happens in your mouth, but Flavor happens in your mind, intellectually.” This is why I cook – not just to produce something which tastes delicious (although, I assure you, this particular dish excites the palate), but for the comfort of food that connects me with my family, my culture, and to a larger global history.

One thing I have learned about comfort food, is that it tends to pop up in variations around the world. Nearly every culture has versions of a healing chicken soup, or a steaming bowl of noodles. These foods were often the food of poverty – simple dishes cooked with care, making the best use of ingredients often harshly rationed.

Although pies can be traced back to the Egyptians in 9500 BC, and potatoes were cultivated over 10000 years ago in Peru, the modern version of shepherds pie is actually a more recent invention. The dish did not become ubiquitous until the potato was heralded as an edible crop in the late 18th century.

In fact, the french name for the dish ‘Hachis Parmentier’ comes from Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, the French scientist famed for studying the potato, and readily advocated it’s nutritional value as a potential boon crop for feeding the poor.

It’s not surprising this dish made it’s way in some version or another around the globe, because it makes successful use of really any type of meaty leftover, and can be made at minimal cost, with little effort. And it is oh-so-satisfying.

My own nostalgia for the dish comes from eating it regularly at my uncle Allan’s table.

Allan grew up in Tangiers, Morocco, and is the consummate host. Family dinners at his house were always a treat. Sometimes there would be fish braised with onions, tomatoes and lemon. Other times, mini meatballs (my favorite) with peas and rice. There were even elegant Moroccan dishes such as b’stilla, a sweet and savory flaky pastry with meat (traditionally pigeon). And of course, there was his Sheperd’s pie.

Curious to its provenance, I emailed my uncle to clarify, and he responded: “Yes, in French it is called hachis parmentier. We never really thought of it as a British dish, or a French one for that matter. We usually called it pastel de patatas in Morocco, and indeed it was a pretty common dish back then.”

Having the chance to recreate a family favorite, and learning more about the global reach of this dish with some delight, I set to work with gusto, making my Hachis Parmentier à la Dorie Greenspan.

So often these days my cooking is limited to recipes of the simplest variety with few steps. After a day of working in a cookbook store, or testing recipes at home, invariably I am too hungry to wait for a slow cooked meal. But with two days off, I set to work making things from scratch, a veritable foreplay for the main event.

My first step was to assemble the broth that is the basis of the filling. This can thankfully be done in advance, so I headed to Drewes, my local butcher shop to purchase the steak that the recipe calls for. Dorie specifies either cube steak or chuck, and because I rarely buy or eat beef these days, I had to clarify with the butcher, shamefully, that chuck roast is the same as chuck steak. (It is.) They packed me up the steak from Marin Sun Farms, and when asked if I would like anything else, I decided the addition of marrow bones would help to enrich my broth, and provide me a tasty snack as a reward for my first day’s work. A few Sicilian sausages went into the bag as well and I headed out.

For the rest of the ingredients, I went to Rainbow Grocery (a vegetarian worker-owned co-op here in San Francisco). My first step was heading over to the cheese department. The recipe specifies using Gruyère, Comté, or Emmental cheese, so I decided to ask the advice of Pete, one of the ever-knowledgeable folks, for a recommendation. After a satisfactory taste, I ended up leaving with a French Gruyère de Comté, made from raw milk and aged for 3 months. (I also could not resist a small piece of Pleasant Ridge Reserve, extra-aged, the recent winner of best in show.)

Wednesday was the perfect afternoon for making broth, my apartment chilly enough that I was still wearing my sweater and scarf. I put my meat, bones, onion, carrot, parsley, garlic, peppercorns and a dash of salt in the pot. I set it to boil, turning it down to a simmer in order not to melt my marrow bones.

After double checking logistics for broth making in both the ‘River Cottage Meat Book‘ and Harold McGee’s ‘On Food and Cooking‘ (and to ensure that I wouldn’t be poisoning myself somehow by boiling bones for just an hour and a half) I sat reading a temporarily stolen Wednesday New York Times food section from my neighbors, as my broth simmered slowly on the stove.

After an hour an a half of simmering, I partook greedily in my wobbly marrow. [Unlike the chicken liver, which I was taught to be polite and share, I take comfort in the fact that nobody in my household now actually eats the stuff other than me.] I packed everything up, cleaned up the kitchen, and headed out to Omnivore to host Michael Chiarello at our little shop.

The next day I picked up where I had left off: sauteing the sausage with tomato paste, adding the boiled beef, and some of the broth until warmed. I spooned the mixture into two individual buttered ceramic ramekins and one larger casserole.

Then I set to work on the mashed potatoes, using some large russets which I peeled, quartered, and boiled in well salted water. There’s nothing that gets me quite as excited as generous quantities of warmed milk, heavy cream, and butter stirred into the tubers. Butter and cream make everything better. After they were done, I spooned them into the ramekins, topped with generous amounts of cheese and baked for a half hour.

The Hachis Parmentier came out of the oven golden and bubbling. The perfect dish for this early fall weather! Devon and I ate contentedly, forking at the layers of salty beef and sausage. The soft carrots had cooked in the broth, and the silky smooth and creamy potatoes were as good as mash gets. Keeping with le French theme, I paired it with some mustard leeks vinaigrette, which provided a nice acidic foil to the richness of the dish.

Recipe: Hachis Parmentier

In accordance with ‘French Fridays With Dorie’ rules, I’m not posting the recipe – you must buy Dorie’s book to get the details. But believe me, it will be money well spent.

by Sam Tackeff | Oct 16, 2010 | Books, Food Travel, omnivore books

(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

I don’t get star struck. There is something about the notion of being starstruck I find completely absurd. Girls going apoplectic over a 15 year old “hottie”? Waiting for five hours in the broiling sun to get a glimpse of an actor? Or stalking your favorite pop star for that matter? I just don’t get it.

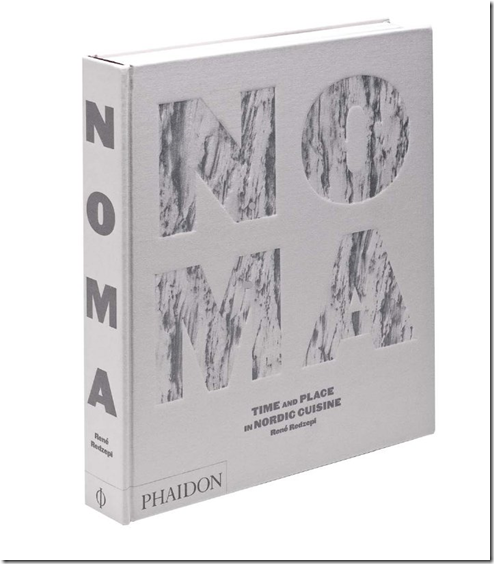

But then again, I’ve been trying to shake the weirdest feeling. One of those feelings where I’ve been run over, had my first kiss, finished a marathon, and won a million dollars… all in the same day. Shit. Is this what being star struck is like? It has been a week since I had the pleasure of hosting René Redzepi here in San Francisco, and I’m still feeling all a quiver.

(Photo: Phaidon Press)

Let’s be clear here, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. With Celia on vacation in Istanbul, I’d been manning the fort at Omnivore for a few weeks. Sure, I had no problem running a few events. Rock Star chefs? I can handle it. No problem Celia!

And then one day it started – a delivery man came with an entire palette of boxes.

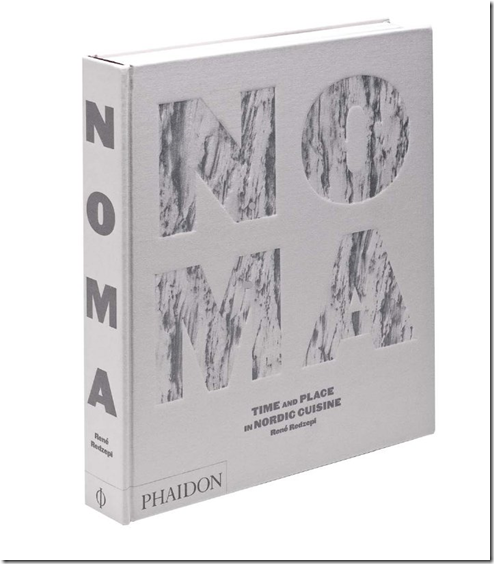

Inside? The Noma Cookbook. 1300 pounds of the Noma cookbook, to be exact. It’s an obscenely beautiful book, put out by Phaidon, weighs nearly five pounds, and is covered in gray cloth. Three quarters of the book are striking photos of the gastronomic creations that have catapulted René Redzepi’s Noma to stardom; this year, Noma has been named the best restaurant in the world.

(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

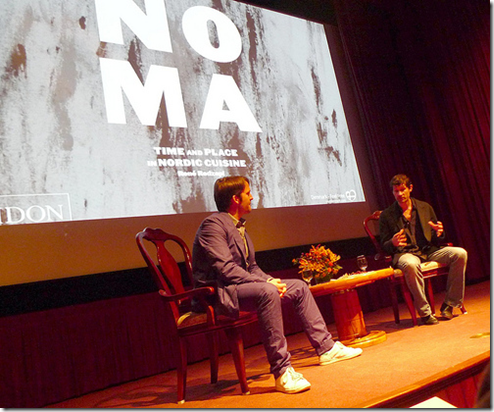

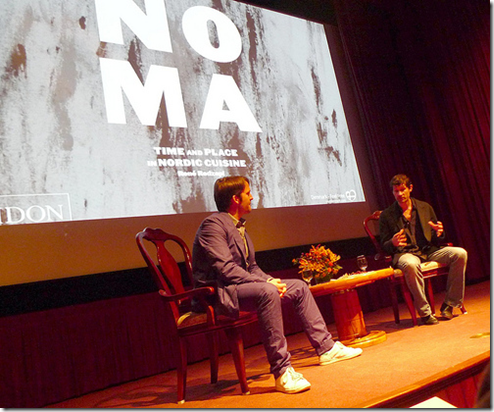

On Sunday night, I couldn’t sleep. Thinking about the Monday lineup was exhausting. A three o’clock signing at the bookstore, close up shop, take all the books and head over to Delancey Street Theater for a two hour talk with Redzepi and Daniel Patterson, check people in, sell books. Racing thoughts kept me awake, terrified. What if I can’t handle it? What if we screw up? What if someone has broken into the bookstore and stolen all 1300 pounds of books — a serious fear brought on by my sleepless delirium.

In hindsight, of course, I had nothing to worry about.

What can I tell you about René Redzepi?

In only a few hours I was able to unequivocally deduce that he is one of the most gracious, intelligent, driven people I have met. (He also has a voracious appetite for knowledge, and snagged some of my favorite historical books on food, including rare copies of Jane Grigson’s Vegetable Book and Fruit Book, and Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook.) He took the time to sign and personalize every book, take pictures with adoring fans, and joke around in between. And he’s adorable.

When he spoke, I took notes – 12 pages of notes – which I’m going to do my best to recount without sounding like a rambling idiot.

René Redzepi and Daniel Patterson Do Stand Up

What happens when you get two chefs on stage together and a captive audience of 150 people? Somehow, they both managed to utter the phrase Seal-Fuckers and everyone finds it hilarious.

For two hours, what unfolded on stage was something incredible. Something I believe everyone will be thinking about for years to come. A combination of a comedy routine, storytelling, and critical analysis. I think it’s safe to say the audience was thoroughly moved by the presentation.

In his introduction, Daniel Patterson – of Coi in San Francisco and the newly opened Plum in Oakland – was clearly excited to be sharing the stage with Redzepi. And who wouldn’t be, really?

Patterson described Redzepi as the master of “cooking from your own place”, and extolled what makes him the best in the kitchen: “Intuition – he’s a scary good cook. Super distinctive and sharp. Watching his mind work? So, so, fast.” To be a chef of this caliber, it is not just about skill, it’s also something deeper. “There’s an incredible warmth, a very strong emotional foundation. There is real joy.”

As the talk commenced, the audience was instructed to look through a little cloth bag under each seat filled with freshly foraged herbs, hay, and a small packet of Angelica root (known in Chinese medicine as Dong Quai). As you opened the bag, fragrance exploded and you were instantly transported to the forest. The bag was so fragrant, in fact, that after leaving it overnight in my leather purse, I’m beginning to believe it has permanently scented my handbag.

It Starts In Childhood

Some of Redzepi’s earliest influences were from an upbringing spent traveling between Denmark and his father’s native country, Macedonia.

In Macedonia, if you wanted food, you grew it. And what you didn’t grow, you traded with your neighbors, or perhaps picked up at the baker. Driven mostly by poverty, but also a sense of pride in their own food, life there was back to the land. The people were poor but not wanting in good food.

It’s not surprising to hear Redzepi didn’t drink soda until he was an adult. Special drinks were syrup over rose petals, or milk (provided that you milked the cow), but mostly, there was water.

In contrast, Denmark in the 1980’s was captivated with the microwave and ready meals. As a child, Redzepi recalled some embarrassment about heading to Macedonia (particularly while his Danish peers were off spending their summers in Italy or France). In hindsight, experiences foraging, farming, and eating from the land have only served him well. His family grew peppers and watermelon. Watermelon, he joked, is the perfect food:”You eat, you drink, and you wash your face”.

But good things don’t last forever, Redzepi lamented, “when the war came, people fled, and slowly as they have returned, life in Macedonia has become more Westernized. They used to sit on the floor, eat with fingers from platters of food as a family, and everything was cooked.” But that is no longer true, and as we are seeing all over the globe, cultural legacies are being lost.

Education Leading up to Noma

When he entered chef college, he became instantly smitten by cuisine. Originally, Redzepi assumed he was going to do his version of French food, but then he went to stage at El Bulli in ’98 – and ’98-2002 was a great time for the restaurant. “For me, I left that place with such a sense of freedom.” From there, he headed West to California for a stage at French Laundry.

At French Laundry, he was further energized. Here was a great Chef [Thomas Keller] with such a strong signature – “An American chef doing something American”, with ingenious dishes like “Coffee and Donuts”.

After traveling the world, the passion to do something new, unique, really something uniquely Danish, was solidified.

And so, seven years ago, he opened his first restaurant, Noma. He was 25.

Noma is located in the Christianshavn area of Copenhagen, Denmark. The building’s original use was as a warehouse for North Atlantic imports, and the rooms that the restaurant is housed in were used to store salt. The owners wanted a chef whose cuisine could in some way reflect the history of the place. And so, Noma moved in, with a noble goal of creating “high gastronomical cuisine using what was around us.”

At the time, basically all top level restaurants in Denmark were using European products. It was the standard. There was such a disbelief in the project. “It’s amazing how little faith we ourselves, the people, had in our own products.”

What unfolded was what Redzepi described by quoting Schopenhauer: “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” (Yes, the only chef I’ve heard quoting German philosophers.)

To put things in perspective about how hard they worked, Redzepi wasn’t happy even receiving their first Michelin star within a year of opening the restaurant. “At first, there were still too many reference points from other cuisines.” The idea of being local is easy. The difficult part is how you take “local” on the plate and make it work.

And so they started seven years ago rediscovering ingredients “so that they taste of their own place”. Chefs often read a lot of recipe books to draw inspiration, but Redzepi found that he needed to start reading other books – history books – to learn what people ate over the ages. And he spent a lot of time talking to historians.

As we listened to Redzepi describe this, Patterson shook his head in admiration: “There is a determination – Rene works a lot. He’s worked his ass off for years. There is a constant pushing.” To which Redzepi replied: “If you don’t have patience and commitment to the extreme and are not manic in your pursuit for this, it can’t happen. You have to work for this.”

Five Dishes

At this point, although I could have listened to hours of just conversation, we got to see a video of five dishes with notes from nature to plate. Most of the dishes at Noma are created with nature as the direct influence. Redzepi explains: “A lot of people ask “why is it so landscape-y?” It’s a reflection of where we go, walk, live….this is just the way things have shaped.”

The cuisine at Noma is so dependent on the weather and the seasons, it can change every day.

Redzepi began by introducing the ingredients he works with: “In Denmark, if there is any prejudice against our region, it’s that it is extremely cold and people think no ingredients can grow. But it’s a matter of determination and hard work.”

Taste is integrally linked to place. He explained (without prejudice) that things in America taste almost overly sweet to his palate – which happens to be because produce here has so much more time in the sun, than in Denmark where the flavors are much more mineralized because the plant gets nutrients mostly from the ground in their harsher climate.

Each dish has its own story, and unfolds with whim and novelty.

There was ‘Asparagus and Spruce’, where the green asparagus tips are grilled, then juiced. They add a touch of spruce oil, and then wrap white asparagus around actual spruce leaves, top with the juiced asparagus, and add a touch of whipped cream.

Or the ‘Steamed Oyster’, composed of the oyster, as well as plants sourced from the land around the oyster flats. So you have these native oysters, and then unripe pickled elderberry, and the dish is created by pouring seawater on, and steaming it in almost its natural environment.

Or “The Sea”, where a dish is composed from sea herbs rich in vitamins, sea water, rocks and beach plants. Topped with dried shaved urchin roe, arranged as if they were in their natural environment.

Or the ‘Hen and the Egg’, where the chef thinks what is a chicken? The whole dish is created from a starting point (the hen house) and the meal is created completely from ingredients a few feet around it. The egg, the hay from the coop, the herbs the hen eats. And then the whole dish is interactive – the diner actually puts together the dish and eats it.

My favorite dish however, was the ‘Vintage Carrot’, because it truly reflected the essence of the creativity on display at Noma.

A vintage carrot is actually a vintage ingredient.

They were having a winter like Ragnarök (the Norse mythological version of Armageddon), and it was “so crazy cold”. The chefs were running out of things to cook at Noma, and were desperately working with their farmers to find something they could serve. One farmer had these old hideous carrots he had left in the ground for a winter, and then stored them in his larder. They were year and a half old carrots. So they thought to themselves, how would you cook a carrot like this?

Maybe like you would cook a piece of perfectly aged beef – with as much care as possible. “So we wanted to do that with a carrot. What would happen if we gave the same care to a shitty old carrot?”

And so here is this dish, composed of vintage carrots, gently cooked with wild chamomile and sorrel in goats’ butter. They cook it, very slowly, an hour, hour and a half, and then suddenly it’s the carrot of their dreams.

And then he thought: SHIT. What if we are now eating the wrong carrots? What if this was the RIGHT carrot? The way carrots are supposed to be? The authentic carrot?

“So we asked the farmer – what other old shit do you have? Give us your crap! And then he got us vintage potatoes…” so the story goes.

CONVERSATION AS THE FOUNDATION

“The importance of people and the importance of conversation is just about everything for us.”

After fully transfixing us with food, the conversation returned to the work they put into the restaurant. Possibly the only frustration I have with the Noma book is that the front section on the day to day happenings of the restaurant is only a handful of pages. (Maybe that’ll be the next book.) Listening to Redzepi, these details are clearly things that he has thought long and hard about.

Noma has 20 full time employees, and 5-8 stagiers (interns – for one to three months) at any time, and the empowerment of each and every team member is an integral part of Noma’s success. The work is highly technical, and many people are involved in each and every dish. All this for forty covers a night. “The kitchen is full of good people, free thinking people – people who take standpoints on what they are cooking,” he went on. “Our trade is one of the last trades that will never be replaced by machines… you need to think”.

In addition to the hard working kitchen staff, they also work hand in hand with the farmers. Noma has a large network of farmers and foragers. They worked hard to cultivate these relationships. Just by giving feedback and respect to the farmers (a group of people, on the whole rarely congratulated for their hard work), they found these people striving to do better. “There is a sous chef in the kitchen to make sure the farmers feel that they are a part of us… They get Christmas cards every year, and every year they are invited to eat at the restaurant. We are having so many conversations with them constantly. If these people were not on the team, we wouldn’t have a restaurant.”

To further the education of his kitchen, Redzepi detailed several ways to make a better chef:

1. Make them harvest, prep, cook & serve. (Instill the feeling of giving.)

Each of the staff at Noma are taught to forage and harvest, which changed how the kitchen thinks about food. Chefs are usually trained to work within the format of recipes, but Redzepi knows first hand that chefs start changing when they really know how things grow. There is something so important about the conversation in nature, “I know it sounds a bit wacky,” Redzepi chuckled, “[but you need to have] a conversation with the plants in the forest. There is something so valuable about learning the essence of taste from the source in its perfect element. You know, the way it should be. How much would you allow yourself to do with this ingredient? [This] reflects how you treat an ingredient in the kitchen.”

How can a restaurant have the same feeling of giving if they charge for their meals? The chef was quick to make note that “in a perfect world, all restaurants would be free”, which he amended: “In a perfect world, all restaurants would be subsidized by the government.” [The audience laughed.]

By requiring everyone to have the opportunity to serve, you create better chefs. Actually seeing guests, they take a better standpoint on cooking. It’s the feeling you get as a parent feeding a child – you want to provide the best and most healthy and perfect food – they adopt the same philosophy for their diners.

2. Every Saturday they have an innovation practice in the kitchen, after service (about 2 am). Everyone has worked 75-80 hours or more. Each section has a head chef who creates a dish – the purpose is to “make chefs take a standpoint on what they enjoy about food.” In the beginning, it is very difficult – but week by week – people get better, stronger. They start really developing themselves as chefs.

This is one of the many reasons chefs around the world fight to work in Redzepi’s kitchen.

* * *

As the conversation neared its close, a member of the audience asked Redzepi “What’s next?” to which he replied:

“The biggest joy is now having complete freedom to cook what we want.” Redzepi laughed, “If we want to put reindeer balls… or beaver snout… we could put it on the menu, and people will try it.” Next is the same… until there is no more inspiration. “I have a personal vision of keeping learning throughout my life, and keeping my family learning.”

“Year by year, season by season, you start to understand more, and it starts adding up.”

* * *

As people filed out of the theater, my admiration was only reaffirmed, as René stood next to me while I sold books, and he personalized them, chatted, posed for photos, and put a smile on peoples’ faces.

Am I star struck? Maybe. A little. But, I’d like to think my jitters came from experiencing a critical moment – one where I was forced to think hard about what I had thought was true. I had to accept something new and profound. After seeing someone with so much passion, dedication, and thoughtfulness, a small part of me regrets not becoming a chef. But for now, I’m taking the time to think about what this will all mean for me. Who knows where life will take me?

And so, here, I share one slightly embarrassing photo that Emily took of us, (give me a break, I’d been working like a fiend the entire day), and would like to take a moment to say thank you to everyone who made this day possible.

Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine (Phaidon Press, $49.95) by René Redzepi, www.phaidon.com